Mtskheta is the ancient capital of Georgia, founded there, "where, merging, they make noise, / Hugging as if two sisters, / Jets of Aragva and Kura." Immediately, in Mtskheta, Svetitskhoveli Cathedral and the tombs of the last kings of independent Georgia, “entrusting” “their people” to the faithful Russia. Since then (the end of the 17th century) the grace of God in the long-suffering country dawns on it - it flourishes and flourishes, “without fear of enemies, / Beyond friendly bayonets”.

“Once a Russian general / Passed from Tiflis to the mountains; He drove a child of a prisoner. / He fell ill ... ”Understanding that in this state he wouldn’t bring the child alive to Tiflis, the general leaves the captive in Mtskheta, in the monastery there. Mtskheta monks, righteous men, ascetics, enlighteners, having cured and christened the foundling, educate him in a truly Christian spirit. And it seems that hard and disinterested work reaches the goal. Having forgotten his native language and accustomed to captivity, Mtsyri is fluent in Georgian. Yesterday's savage "ready in the color of years to pronounce a monastic vow."

And suddenly, on the eve of the solemn event, the priemysh disappears, quietly slipping out of the monastery fortress at the terrible hour when the holy fathers, frightened by a thunderstorm, crowded like lambs around the altar. The fugitives, of course, are sought by the entire monastery army and, as expected, for three whole days. To no avail. However, after some time, Mtsyri still accidentally finds some strangers - not in the depths of the Caucasus Mountains, but in the immediate vicinity of Mtskheta. Having identified the young man of a monastic service lying on the bare earth scorched by the heat of nakedness, they bring him to the monastery.

When Mtsyri comes to his senses, the monks initiate an interrogation. He is silent. They try to force-feed him, because the fugitive is exhausted, as if he had suffered a long illness or exhausting labor. Mtsyri refuses food. Having guessed that the stubborn was deliberately rushing his “end”, they send to the Mtsyr the same little man who once went out and christened him. The kind old man is sincerely attached to the ward and really wants his pupil, since it is written to him to die so young, fulfilled the Christian duty, humbled himself, repented and received absolution before his death.

But Mtsyri does not at all repent of a daring act. On the contrary! He is proud of him as a feat! Because in the wild he lived and lived like all his ancestors lived - in alliance with the wild - vigilant as eagles, wise as snakes, strong as mountain leopards. Unarmed, Mtsyri engages in combat with this royal beast, the master of the local dense forests. And, having honestly defeated him, he proves (to himself!) That he could “be in the land of his fathers / Not from the last daredevils”.

The feeling of will returns to the young man even that which would seem to have forever taken away captivity: the memory of childhood. He recalls his native speech, and his native village, and the faces of his relatives - his father, sisters, brothers. Moreover, even for a brief moment, life in alliance with wildlife makes him a great poet. Telling Chernets that he saw what he experienced while wandering in the mountains, Mtsyri selects words that are strikingly similar to the pristine nature of the mighty nature of the fatherland.

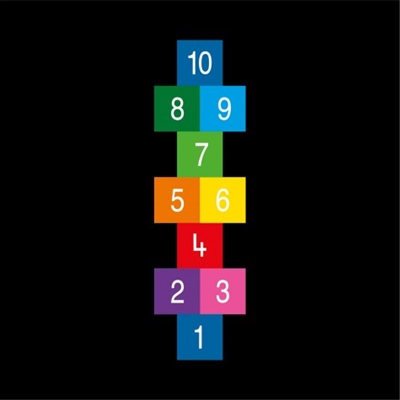

And only one sin weighs on his soul. This sin is an oath of crime. After all, once, long ago, as a young man, a fugitive swore to himself a terrible oath that he would run away from the monastery and find the path to his native land. And so he seems to be following the right direction: he is walking, running, racing, crawling, climbing - east, east, east. All the time, day and night, in the sun, in the stars - east of Mtskheta! And suddenly he discovers that, having made a circle, he returned to the very place where his escape began, the feat of Escape, in the immediate vicinity of Mtskheta; from here it’s a stone's throw to the monastery monastery that sheltered him! And this, in the understanding of Mtsyri, is not a simple annoying oversight. The years spent in the “prison”, in the dungeons, and this is exactly how the monastery takes it, not only physically weakened his body.

Life in captivity extinguished in his soul a “guide-ray”, that is, the unmistakably true, almost animal feeling of his path, which every mountaineer has from birth and without which neither a person nor an animal can survive in the wild abysses of the central Caucasus. Yes, Mtsyri escaped from the monastery fortress, but he will not be able to destroy that inner prison, the constraint that the civilizers built in his soul! It is this terrible tragic discovery, and not the lacerated wounds inflicted by the leopard, that kills the instinct of life in Mtsyri, the thirst for life with which the true, and not adopted children of nature come into the world. A born freedom lover, he, in order not to live as a slave, dies like a slave: humbly, cursing no one.

The only thing he asks his jailers for is to be buried in that corner of the monastery garden, from where "the Caucasus is visible." His only hope for the mercy of a cool, breezing mountain breeze is to suddenly bring to the orphan's grave a faint sound of native speech or a fragment of a mountain song ...